Cross Creek (film)

| Cross Creek | |

|---|---|

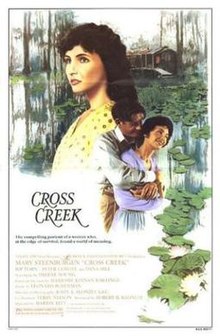

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Martin Ritt |

| Screenplay by | Dalene Young |

| Based on | Cross Creek by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings |

| Produced by | Robert B. Radnitz Martin Ritt Terence Nelson |

| Starring | Mary Steenburgen Rip Torn Peter Coyote Alfre Woodard Dana Hill |

| Cinematography | John A. Alonzo |

| Edited by | Sidney Levin |

| Music by | Leonard Rosenman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures Associated Film Distribution Corporation |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 127 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8 million[1] |

Cross Creek is a 1983 American biographical drama romance film starring Mary Steenburgen as The Yearling author Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. The film is directed by Martin Ritt and is based in part on Rawlings's 1942 memoir Cross Creek.

Plot

[edit]In 1928 in New York State, aspiring author Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings advises her husband that her last book was rejected by a publisher, she has bought an orange grove in Florida, and she is leaving him to go there. She drives to the nearest town alone, and arrives in time for her car to die. Local resident Norton Baskin takes her the rest of the distance to a dilapidated and overgrown cabin attached to an even more overgrown orange grove. Despite Baskin's (and her own) doubts, she stays and begins to fix up the property.

The local residents of "the Creek" begin to interact with her. Marsh Turner comes around with his daughter Ellie, a teenage girl who keeps a deer fawn as a pet named Flag. A black woman, Geechee, arrives and offers to work for her, even though Rawlings insists she cannot pay her much. The grove languishes below her expectations and Rawlings writes another novel, hoping to get it published. A young married couple moves into a cabin on Rawlings's property. The woman is pregnant and they reject Rawlings's attempts to help them.

Rawlings employs the assistance of a few of the Creek residents, Geechee and Baskin, to unblock a vital irrigation vein for her grove, and it begins to improve. The young couple has their child. Ellie's deer grows older and escapes her pen, and Marsh foretells that the deer will have to be killed for eating all their food. Geechee's husband comes to stay with her after being released from prison, and Rawlings offers him a place to work in her grove, but he refuses and Rawlings asks him to leave.

Even though her husband drinks and gambles, Geechee goes to leave with him, and Rawlings admits she will be sad to see Geechee leave, after Geechee demands to know why Rawlings would allow a friend to make such a mistake. Geechee decides to stay after all after telling Rawlings that she should learn how to treat her friends better.

Rawlings submits her novel, a gothic romance, to Max Perkins, and it is rejected again. He writes to ask her to write stories about the people she describes so well in her letters instead of the English governess stories she has been writing. She does so immediately, beginning with the story of the young married couple (which eventually becomes "Jacob's Ladder," published in Scribner's Magazine in 1931).

During a visit to the Turners' home on Ellie's 14th birthday, Flag escapes his pen once more and Marsh is forced to shoot him after he eats the family's vegetables. Ellie screams at him in hatred, and Marsh goes on a bender, goes into town and attracts the sheriff's attention. The sheriff finds Marsh drinking moonshine with a shotgun across his lap and demands the gun. When Marsh offers it to him, the sheriff shoots him. The story becomes the basis for The Yearling.

At Marsh’s funeral, Ellie blames Rawlings for Marsh's and Flag’s deaths and tells her to leave. Rejected and heartbroken, Rawlings leaves her home in a motorboat and rides down the waterways for several miles. After more than a day in complete isolation and loneliness out in the water, she returns to her home and is happily reunited with Geechee. A few nights later, Rawlings and Geechee find themselves battling to save their orange grove from the autumn frost. The neighbors arrive to help her out, and among them are Ellie and her younger siblings. Ellie apologizes to Rawlings for her behavior at Marsh's funeral, stating that “good friends shouldn’t keep apart,” and they reconcile.

Perkins visits and accepts her story "Jacob's Ladder" upon reading it. Baskin asks Rawlings to marry him, and she accepts after much hesitation about her independence. Rawlings realizes her profound attachment to the land at Cross Creek.

Cast

[edit]- Mary Steenburgen - Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

- Rip Torn - Marsh Turner

- Peter Coyote - Norton Baskin

- Dana Hill - Ellie Turner

- Keith Michell - Preston Turner

- Alfre Woodard - Beatrice "Geechee"

- Malcolm McDowell - Max Perkins

- Joanna Miles - Mrs. Turner

- Ike Eisenmann - Paul

- Cary Guffey - Floyd Turner

- Toni Hudson - Tim's Wife

- Bo Rucker - Leroy

- Jay O. Sanders - Charles Rawlings

- John Hammond - Tim

Production

[edit]In 1928 Rawlings gave up a ten-year career in journalism to move to Cross Creek and write novels. She won the Pulitzer in 1939 for The Yearling.[2][3]

Rawlings' book Cross Creek was published in 1942. The New York Times called it "an autobiographical regional study".[4] Reviews were strong and the book became a best seller, selling more than 500,000 copies.[5] A companion book Cross Creek Cookery came out the same year.[6]

In 1943 Miss Zelma Gaison, a social worker and friend of Rawlings, sued the author for $100,000 alleging defamation of character in the novel, claiming it made her look like a "hussy" who "cursed".[7] The suit was initially dismissed.[8] However Gaison appealed to the Supreme Court, who referred the matter to a jury, saying there was an arguable case of invasion of privacy.[9] The jury ruled against Rawlings but awarded the plaintive only $1.00 in damages. This action soured Rawlings on Cross Creek and led to her leaving the area.[10] Rawlings died in 1953.

Development

[edit]Film rights were purchased by producer Robert Radnitz. "There was such a feeling of place in the book," he said. "That's something that has always interested me, because I think all of us are very influenced by where we happen to live. Second, I felt that what she accomplished was incredible, particularly at the time she did it. It took tremendous courage for her to pick up and start a new life."[1]

In 1978 Radnitz announced he would make a TV movie of the book for NBC with Elizabeth Clark to adapt it.[11] The film was not made.

Radnitz decided to make a feature film instead and got Dalene Young to write a script. "The script was turned down by every major studio in town," said the producer. "They all said to me, 'God, it's beautiful. Come back if you've got Jane Fonda or Meryl Streep.' One of them literally suggested Barbra Streisand. I said to him, 'Can you really imagine Barbra Streisand in this role?' He said, 'Well, I admit it's off-casting, but it could be interesting'."[1]

Eventually he succeeded in getting Martin Ritt, with whom he had made Sounder, to direct and financing was obtained from EMI Films.[1]

It was one of a number of films Ritt had made about the South. "The essence of drama is change," he said, "and the South has gone through more changes than any other section of the country."[1]

Casting

[edit]In 1982 it was announced Mary Steenburgen would star and Steenburgen's husband Malcolm McDowell was to play editor Max Perkins.[12]

Ritt says he cast Steenburgen because "I wanted a lady out of Middle America who had a lot of the good qualities associated with that section of the country... I just thought she was right. It's an educated guess, you never really know. You try to pair the actors together with the big scenes. I knew Mary was good. I'd seen Melvin and Howard... I just had a feeling she'd be right."[13]

The character based on Jody was a girl in real life and turned into a boy for The Yearling. The filmmakers were going to keep Jody a boy for the film until they saw Dana Hill in Shoot the Moon and changed it to a girl.[14]

Radnitz suggested Rip Torn, with whom he had worked on Birch Interval, as the backwoods hunter, Marsh Turner. When Alfre Woodard auditioned for her role Ritt says "Alfre just blew us all away. Everybody was crying when she left. Her power is extraordinary."[1]

"I don't think this role is demeaning at all," said Woodard. "It wasn't written that way. It could have been portrayed in a less sensitive light. But that would depend on what the actor brought to it. I thought this woman was quite wise and very much in touch with the earth. She was alive and I fell in love with her immediately. I wasn't prejudiced against her because she had to work for a white woman for a living, which any Black woman, even myself, would have had to do if she'd lived in Florida in 1925. I wasn't going to hold it against her and I wasn't going to try to portray, through that woman, my frustrations with the politics in this country."[15]

Shooting

[edit]Filming took place at Ocala, Florida, near Mrs. Rawlings's house, which is now a state museum. The unit had to deal with mosquitos, snakes, alligators and rainfall. "I felt I was being bitten by the same mosquitos and hearing the same sounds as Marjorie Rawlings," said Steenbergen.[1]

Radnitz said the location was almost another character in the film.[16]

Rawlings's husband, Norton Baskin, the hotel proprietor whom she met when she moved to Florida played by Peter Coyote in the film, came on location several times. He also had a cameo as the elderly man who directs Marjorie to Norton Baskin's hotel. "I was tickled to death when I met Peter Coyote," said Baskin. "He was macho as hell, which I wasn't. He is 6 foot 1, handsome and athletic, whereas I'm 5 feet 8 and anything but. I always wanted to look like that."[1]

"A lot of people down there really glorified and romanticized Marjorie, whereas Norton tended to be real straight about her," said Steenburgen. "It's very easy to approach a character like that - a so-called strong woman who overcomes the odds - and give a one-note performance, playing that strength alone. Strength is only one thing a person has. I'm real strong, and I'm also real feminine, and I don't find a struggle having those two things under one roof. Norton helped me to see that the same was true of Marjorie."[1]

Steenburgen said, "The movie is about what it takes to make a writer write - it's essentially an internal struggle - and it's very hard to do that, to be that quiet. Technically, I never found a key to it, but I did understand her compulsion, her passion. She was - I don't know a pretty phrase for it - emotionally constipated, and didn't feel she could be part of anything until she proved herself as a writer."[17]

"Writing is essentially an internal process," said the star. "To try to make that external has always been a trap for actors. You tend to get self-indulgent and overly dramatic. I don't know if I licked the problem, but I don't think I make people cringe. I tried to show her passion for wanting to be the best writer she could possibly be."[1]

"I'm sure some critics will feel we haven't dramatized the creative process," said Ritt. "But that's really not what this picture is about. It's about a community and its people and their impress on Marjorie Rawlings. Fundamentally, it's about the land, because that's what inspired Marjorie and gave her a chance to fulfill herself."[1]

"I love Cross Creek," Steenburgen said. "I think it's a much more wonderful movie than what I ever expected. Some movies are like home movies to the people who participated in them, and that's what Cross Creek is like for me. I watch the scenes with Rip (Torn) and remember what it was like doing them. It's so much fun working with him. You're never quite sure what you're going to get with him. You know it's going to be something truthful. A scene was always lively when he was in on it because he was so unpredictable. You had to be ready for anything. It's a nice fright, though. The kind of fright every actor hopes for."[13]

Differences from real life

[edit]The film fictionalised elements of Rawlings life:[18]

- She did not leave her first husband and come to Florida to write alone; they worked for four years growing oranges in Florida before the marriage broke up.

- Baskin did not meet her when her car broke down and he did not fix it up.

- Her maid was unlike the character in the movie.

Also Baskin is only mentioned a few times in the book but makes up a major part of the film.[18]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]Ritt says he knew the film would be challenging commercially. "No one in middle America is wildly concerned about the dilemma of the artist," he said.[1]

The film performed poorly at the box office.[13]

Critical reception

[edit]Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 61% based on 18 reviews.[19]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[20][21] | Best Supporting Actor | Rip Torn | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actress | Alfre Woodard | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Joe I. Tompkins | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Leonard Rosenman | Nominated | |

| Cannes Film Festival[22] | Palme d'Or | Martin Ritt | Nominated |

| NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture | Alfre Woodard | Won |

| National Board of Review Awards[23] | Top Ten Films | 9th Place | |

| Young Artist Awards[24] | Best Family Feature Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Young Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture | Dana Hill | Nominated | |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l ALLIGATORS WEREN'T THE ONLY OBSTACLES TO 'CROSS CREEK' Farber, Stephen. New York Times 18 Sep 1983: A.15.

- ^ 'The Yearling,' Prize Novel, Tells of 'Cracker' Schoolboy: Story of Cracker Youth Miami Daily News Wins The Christian Science Monitor 2 May 1939: 4.

- ^ Only One Road to Success--Says Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: Hard Work, Declares Author of "The Yearling," Pulitzer Prize Novel, Is Only One She's Found Modest and Unassuming A Journalist Ten Years Her Working Habits Her Hobby Is Cooking Neighbors Love Her Jody" Well Chosen By Sarah Shields Pfeiffer Written for The Christian Science Monitor. The Christian Science Monitor 4 Sep 1940: 7.

- ^ Books of the Times By ROBERT van GELDER. New York Times 16 Mar 1942: 13.

- ^ Best Sellers of the Week, Here and Elsewhere New York Times 23 Mar 1942: 13.

- ^ Cross Creek: Here Comes Mary Meade Meade, Mary. Chicago Daily Tribune 15 Nov 1942: H21.

- ^ CHARACTER' -- SUES WRITER: Social Worker Asks $100,000 of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings New York Times 3 Feb 1943: 21.

- ^ Suit Against Author Of 'Cross Creek' Off The Christian Science Monitor 1 Sep 1943: 2.

- ^ BOOK SUIT TO BE RETRIED: Miss Rawlings' Writing of 'Cursing' Woman Will Go to Jury New York Times 25 Nov 1944: 17.

- ^ Mrs. Rawlings Wins Verdict New York Times 29 May 1946: 6.

- ^ 'Cross Creek' Set for TV Los Angeles Times 28 Sep 1978: e24.

- ^ Dateline HollywoodBy Steve Pond. The Washington Post 04 Mar 1982: C7.

- ^ a b c FOR ACTRESS, FANTASIES ARE NOW REALITY Lyman, Rick. Philadelphia Inquirer27 Nov 1983: K.1.

- ^ MGM-UA SETS GUIDELINES FOR COST OF MOVIES: FILM CLIPS Pollock, Dale. Los Angeles Times 26 Mar 1982: h1.

- ^ Positive Thinking White, Ernest P, Jr. Washington Informer Washington, D.C. Vol. 19, Iss. 51, (Oct 12, 1983): 15.

- ^ CROSS CREEK Laursen, Byron. Los Angeles Times 29 Apr 1983: n14.

- ^ Little Mary from Little Rock finds happiness Scott, Jay. The Globe and Mail20 May 1983: E.1.

- ^ a b THE MAN AT CROSS CREEK IT WASN'T EASY BEING MARRED TO MARJORIE KINNAN RAWLINGS. JUST ASK HER HUSBAND -- WHOSE STORY ISN'T IN ANY BOOK OR MOVIE Flood, Danielle. Sun Sentinel; Fort Lauderdale 8 Sep 1985: 27.

- ^ "Cross Creek". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ "The 56th Academy Awards (1984) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ THE OSCAR CHASE: A PEEK BEHIND THE SCREEN HARMETZ, ALJEAN. New York Times 8 Apr 1984: A.19.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Cross Creek". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ "1983 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "5th Youth In Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Archived from the original on 2011-04-03. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

External links

[edit]- Cross Creek at IMDb

- 1983 films

- American romantic drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- Films scored by Leonard Rosenman

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films directed by Martin Ritt

- Universal Pictures films

- Biographical films about writers

- EMI Films films

- American biographical drama films

- 1980s American films

- English-language biographical drama films